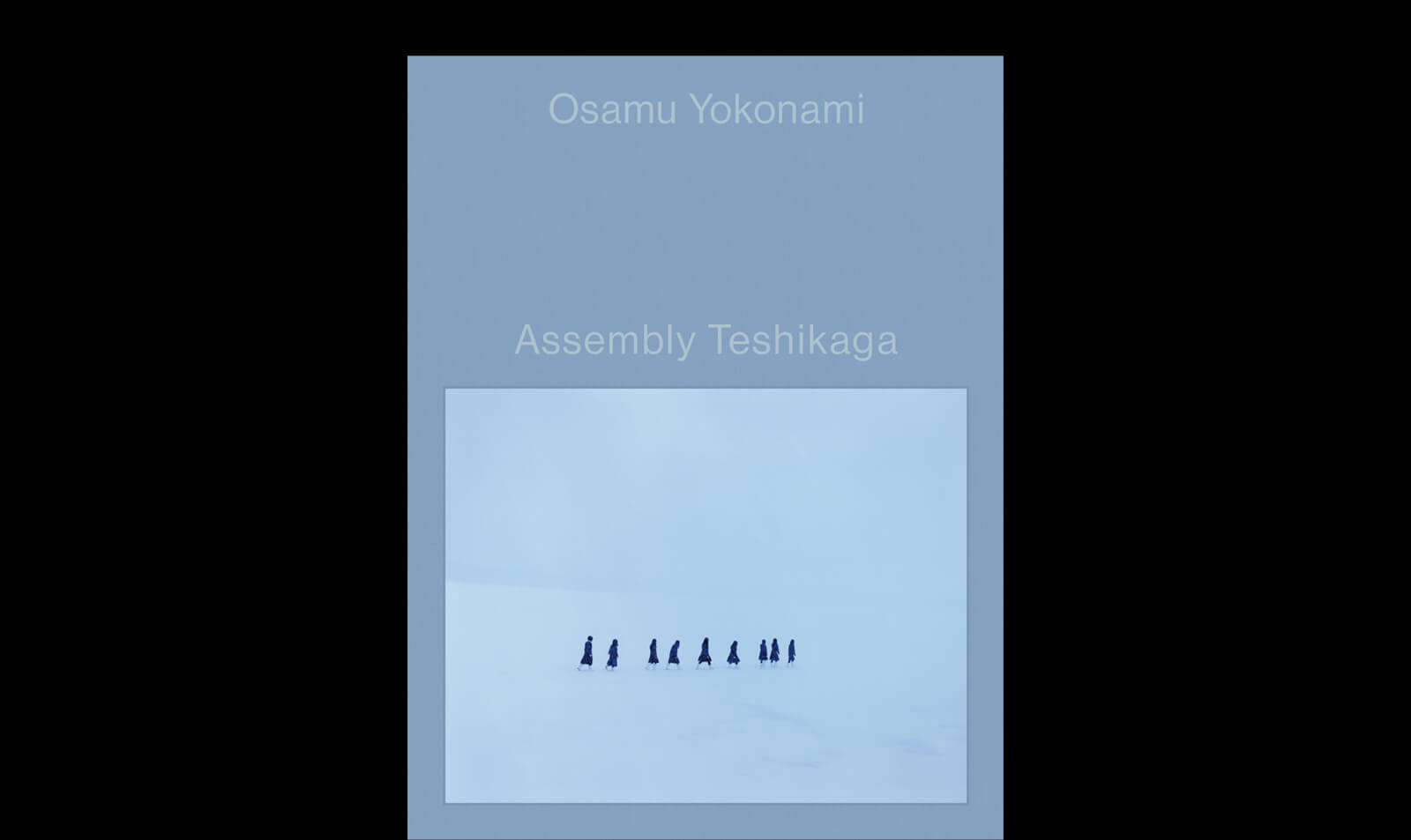

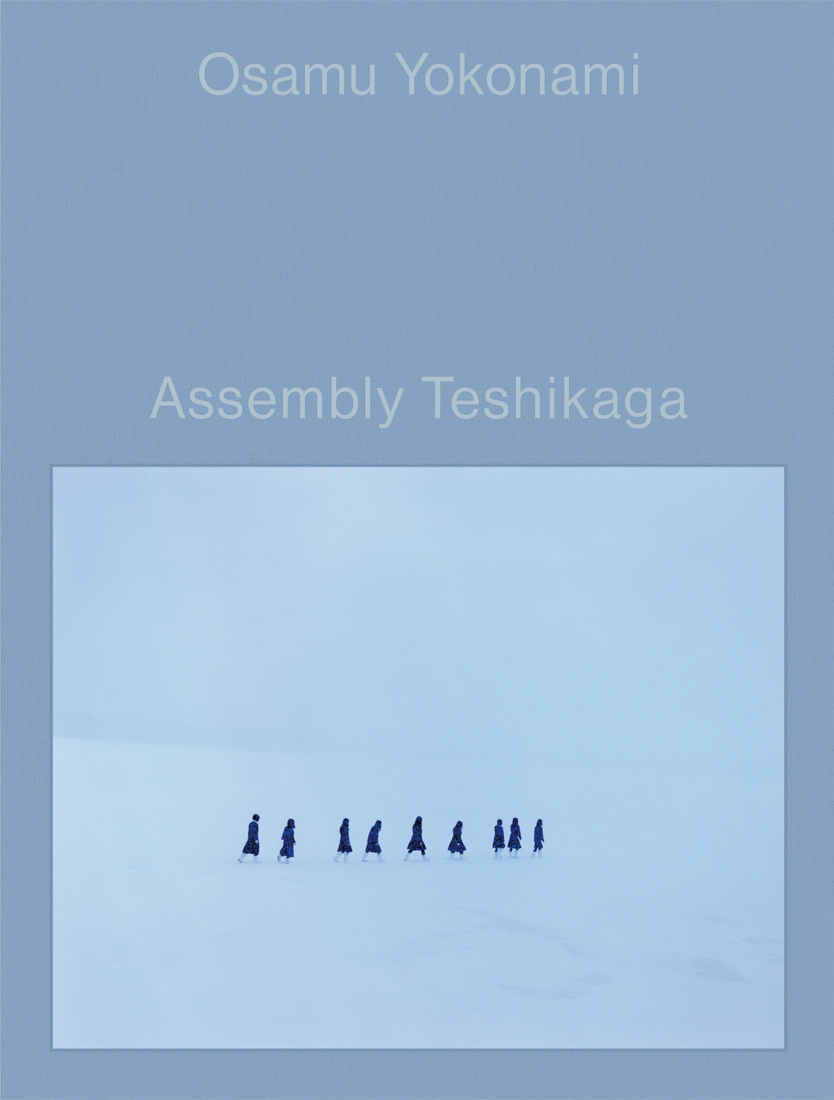

出版プロジェクト「Lula BOOKS」の第4弾となる、写真家 横浪修の作品集「Assembly Teshikaga」が10月18日(水)より発売。

これを記念した写真展が、10月19日(木)から11月7日(火)までBOOK AND SONSにて開催される。

今回Lula Japan Webでは、発売に先駆けて横浪にスペシャルなインタビューを実施。

写真家の道を行くと決めてから経験してきた、

さまざまな出会いや環境の変化、時折立ちはだかる大きな壁。

そんな中でも揺らぐことのない確固たる決意。

着実に歩みを進めていく上で感じてきたものを

ひとつひとつ丁寧に、率直な言葉で語ってくれた。

−初めてカメラを手にしたのはいつですか。

写真を好きになったきっかけについて教えてください。

小学生の時に親がKonicaのカメラを持っていて、家族で出かけた時に自分で撮ったりしてました。

その時は全然ハマっていなかったんだけど。

きっかけは中学2年生くらいの時に西田敏行さんが演じる通信社の専属カメラマンが主人公の「池中玄太80キロ」というテレビドラマを見て、午前中にボスから「今から北海道に行ってくれ」と言われて午後に北海道に行くシーンがあったんですよ。

自分の親は自衛隊だったんで、小さい頃普通の会社員は会社に行って机に向かう仕事だと思っていたから、仕事で色んなところに行けるのがいいなって。

カメラマンっていいなっていうのがただありましたね。

−カメラにハマった当初はどういった写真を撮られていましたか。

当時CAPAというカメラ雑誌を見て、風景とか、見様見真似で何も意識せず写真を撮ってました。

それから高校1〜2年生くらいの時に親に一眼レフを買ってもらって、本格的に写真を撮るようになりました。

その頃から漠然と写真の専門学校に行くと決めていて、周りからは「カメラなんて勉強してどうするの?」と言われてたんですけど。

結局やればできるというか、はなから諦めてたらできなくなってしまうので。

−写真家の道を進んでいく中で大変だったことはありましたか。

アシスタントの時はお金もないし、大阪にいた時も大変でしたね。

先が見えないから、どうなるか分からなかった。

今の時代って自分で発信したら仕事になったりするかもしれないけど、昔はもっとハードルが高かったから。

カメラマンってなれたらいいけど、なれなかったら結構しんどいので。それでもやろうとしないとなれないし、ずっとやり続けるしかないかなって。

大阪にいた時に一度関係ない仕事をしていて、写真が嫌になった時があったんですよ。

最初は専門学校を出て会社案内や入学案内を扱っている出版社に就職して、会議風景や工場の機械、顔写真を撮ったりしてました。

働いたことがなかったんで、月曜から土曜まで毎日朝から晩までずっと仕事があって、日曜日も月に2回くらい仕事があったからほとんど休みがなくて、働くのって結構大変だなって思いました。

その後個人のカメラマンのアシスタントに就いてたんですけど、朝から晩まで事務所にいてもやることがあまりなくて、お金も厳しくて貯金を崩したり、夜に印刷会社のバイトをして、何でこんなことしてるんだろうって、だんだん心が荒んでいった。

結果その師匠のところをやめてまた違う仕事をしてたんですが、半年ぐらいしてやっぱりまた写真を撮りたいなって思った。

そこから街中の会社の倉庫みたいな一軒家の2階に住んで、東京に行くためにお金を貯め始めた。その家がまた汚くて、倉庫にイタチが出たりもしましたね。

それでもカメラマン以外の仕事はないなと、22歳ぐらいの時に覚悟ができた。

−東京に行きたいと思ったきっかけは何かあったのですか。

当時、専門学校を卒業したらみんな東京のスタジオに入ってたんですよ。

自分はその人たちより2年くらい遅れて東京に行ったんで、後輩になるのは嫌で文化出版局の写真部に入りました。出版社だったら誰もいないだろうって。

やっぱりファッションの人やカメラマンも第一線で活躍する人、海外帰りの人とか色んな人が来るんで刺激的でしたね。

その時はまだバブルの時代で、すごい世界だった。

−周りの環境が劇的に変わっていく中で、心境の変化はありましたか。

写真家になるという覚悟はずっと変わりませんでした。

今はもうないんですけど、当時は6階建てくらいの文化出版局というビルがあったんですよ。

編集者は「COMME DES GARÇONS」や「YOHJI YAMAMOTO」とか黒い服を着た人ばっかりで、そういう時代だった。

2階が総務で、3〜4階に編集部が入ってて、5階がメイクルームとスタジオ、6階が写真部みたいなところがあって。そのスタジオに行くまでに外部の人とか、皆が通る廊下があったんですね。

それである時部長にそこに自分の写真を貼っていいか聞いたんです。

今までそういうことをやっている人がいなかったんですが、自分の写真を編集の人に見てもらえたらいいなって思って。

その後中込一賀さんのアシスタントに1年半くらい就いてて、MR.High Fashionという雑誌でタイに行く企画があったのね。

多分当時の編集長が廊下に貼っていた自分の写真を見てくれてたのか、声をかけてくれて、師匠の撮影とは別で取材とドキュメンタリー写真の仕事をアシスタントだった自分に振ってくれたんです。

その頃アシスタントは師匠よりも3日ぐらい前に現地に行って準備をしなきゃいけなくて。

先にタイに行って、1日だけバンコクのチャオプラヤ川の川沿いをライターの人と歩きながら写真を撮るというとても贅沢な企画だったんですが、最終的に12ページくらいになったんです。

そんなのアシスタントだった自分にとってはすごいことで、師匠のファッションページと組み合わせたレイアウトになってて。

自分の写真はドキュメンタリーだったから、ファッションよりも強く見えた。

このチャンスがあったのも自分が文化出版局にいた時に種を撒いていたことが1〜2年後に繋がったからで、やっぱり常に思ったらやった方がいいなって思いました。

とりあえず撮り続けて、評価されるのは後からついてくる。

−継続的に作品集の出版や、国内外問わず精力的に活動の幅を広げられていますよね。

個人的に自分がやってることと、日本の写真の世界って違うように感じます。

日本だとマニアックな世界が受け入れられるのは難しいし、自分は海外から出した方が良いとか。

例えば自分が商業的にやっている写真は日本だと認知されているけど、海外だと知られていないからフラットな目で見てくれる。

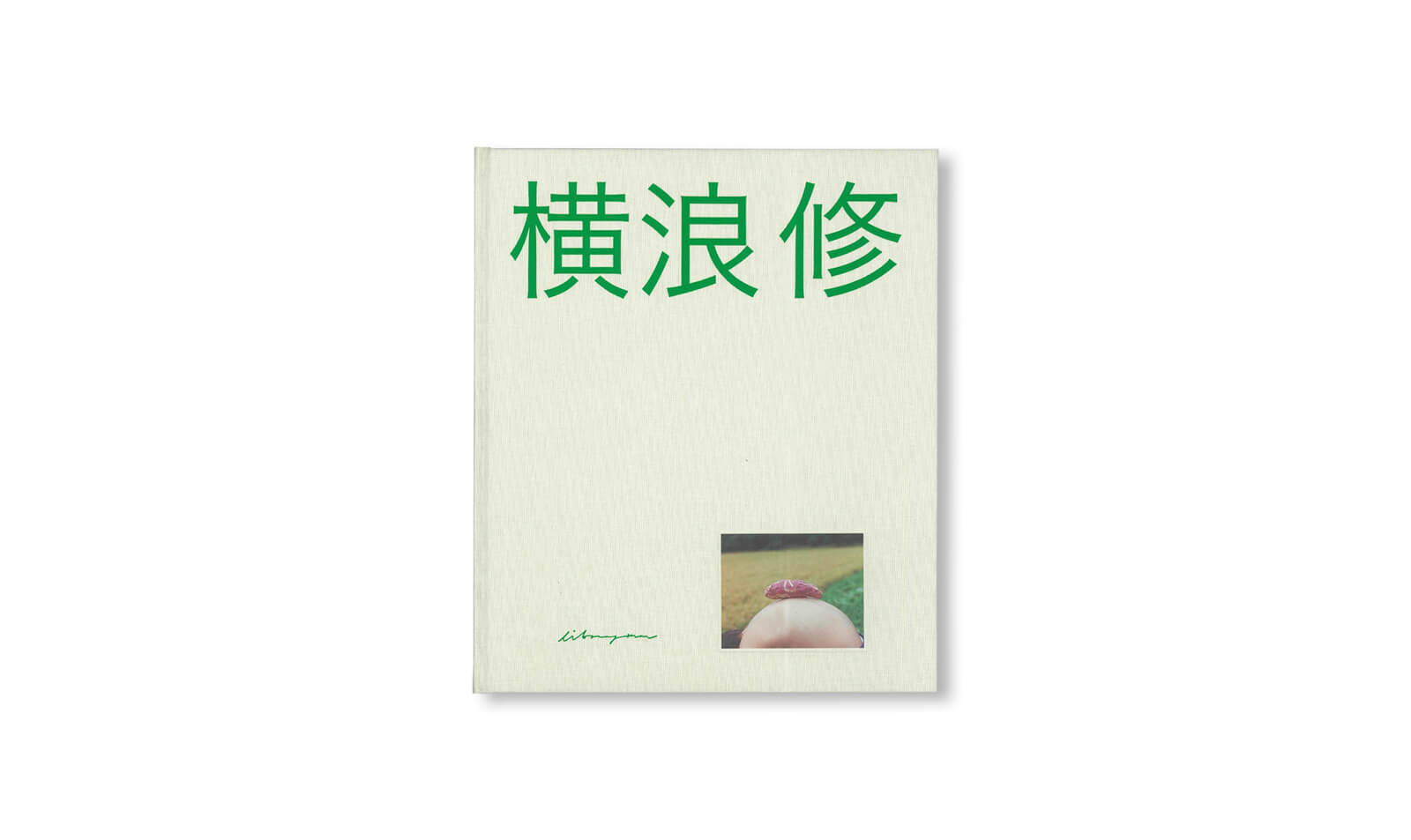

Librarymanから写真集を出版したりとか、海外でチャンスがあったらどんどん乗っかっていく。

そうしていくうちに海外でも認知されていくようになって、重ねていくと総合的に見て1つの塊になって、強度のあるものになっていく。

やっぱり続けていくしかないのかなと思いますね。

−子どもたちがフルーツを肩に挟んだポートレート作品のシリーズや、今回出版された「Assembly」 のシリーズも撮り続けられていますよね。

色んなことをやっていくよりも、何かをしつこく特化してやっていったほうが誰にも追いつけないところに行けるというか、何かを強化していった方が良いかなと自分の中で思ってる。

最近中国で仕事をしたのも、自分のことを認めてくれたから。

15人くらいの子どもの撮影だったんですけど、全然言うことを聞いてくれなくてめちゃくちゃ大変だった。

でもそうやって海外の仕事ができているのも、何十年か種を撒いてきたことが繋がっているんだと思うんです。

−1番好きな国はどこですか。

タイとか好きです。食べ物が美味しくて。

街も人であふれてて、昭和の30〜40sくらいの雰囲気があって居心地が良くて、人がニコニコしてる。

人が優しいっていうか、バンコクが好きですね。

−最初の色々なところに行けるからカメラに興味を持ったことにも繋がってきていますよね。

確かにそうですね。

あとは色んなことや色んな人を反面教師にしています。

カメラマンが第一線で何十年もやっていくのは難しい。

売れてくるとちょっと言い方が大柄になったり、仕事が雑になったりする人がいるじゃないですか。そういうのを気をつけながら仕事をしているのはありますね。

もしかしたら自分も若い時は多少そういうふうになってたかもしれないけど、自分のアシスタントにもそうなったらダメだと伝えてます。

20代から30代までは日本のファッション誌をほとんどやってたので、テーマが被ってきたりもしました。そうなるとやることもだんだん追い詰められていって、このまま雑誌だけやっていくのはダメだと思う時期もあった。

そこから意識して30代前半から33、34歳くらいの時、雑誌をセーブしながらチャンスがあったら広告の仕事もやってきたけど、昔のカメラマンは雑誌の人と広告の人ですごく分かれていたんですよ。

当時は広告カメラマンの方が上のイメージがあったから、そこに行くのはすごく難しくて。自分でプロデューサーの人を紹介してもらって、ブックを見せに行ったりもしたけれど、100人に1人くらいしか頼めないだとか、打ちのめされて嫌な思いもした。

その時に作家みたいな活動もしたいから、ある出版社に自分が撮った作品をまとめて持って行ったら、「写真集を作りたいのか、仕事としてやりたいのかどっちがしたいんですか?」と言われたことがあってね。

そういう風に見られるんだと思って。

雑誌とかでの仕事は完全に自分で作ったものではなくて、誰かと協力してやっているし、お金が発生してるからまったく別物だと考えてた。

それからまずは自分で形にして頼みたいと思われるようにならないとダメだなと思って、意識的に作品を作るようになりましたね。

−ファッション撮影と作品撮りに取り組む上で、何か考え方など違うことはありますか。

自発的か自発的じゃないか、ファッションはその服をどう見せるかとかがありますよね。

あとはチームで作り上げるので、他の人の意見が入る。

雑誌だとある程度テーマが決まっているから、そこに基づいてやるというか。

でも作品は自分から生み出すものだから、何でもありで、360度方向性がある。

自らの意思決定がすべてだから、取捨選択したものが全部自分に返ってきますね。

−正直どちらの方が大変ですか。

意外に頼まれてやる方がある程度方向性が決まっているから楽かもしれません。

でも今は自分の作品の方向性もできているので、そこに何か目標を設定して逆算して撮るだけ。

作品って何を撮ったらいいか分からないと皆言うんですけど、自分がそこの選択で何を選ぶか自体からもう始まっているので、あとは生み出すしかない。

例えばトイレに行った時とか、お風呂でぼーっとしてる時とか、ふとした瞬間に「何かこれいいかも」って思って、とりあえず試しにやってみるんですよ。

自分の中で手応えがあると続けてやる。

全部思いつきなんです。

−アイデアを考える上で、何か意識的にインプットしてる習慣はありますか。

前はよく時間がある時は代官山 蔦屋書店や青山ブックセンターに行って海外誌を読んだり、展示に行ったりしてました。

ファッション雑誌はヴィジュアルに流行りがあるから、ライティングとか、撮り方とかも違うので参考にしてた。

何となく自分の写真は、昔からその都度変わってきているんですよ。

例えば皆が流行りに乗ってやっているライティングを、半年遅れて乗っかったりして。

昔、日本で東京の街をロンドンやパリっぽく撮るのが主流で良しとされていた頃もあったけど、それに対しては疑問があった。

日本人なんだから、日本人しかやれないことを発信した方がいいのかなと。

荒木経惟さんとか森山大道さんとか世界で受け入れられているのは、日本のオリジナリティがあるから。

全然作風は違うけど、そういうことには憧れる。

意識して、日本人だから撮れることをやろうと思って、自分は「1000 Children」とかやっているのはあるけどね。

−今はどのようにインプットしていますか。

インスピレーションをもらえるアーティストやクリエイターはいますか。

あまり意識はしてないけど、電車や自転車に乗ったり、街を歩いたり。

そういった習慣から色々な発想は得ているような気がします。

あとは結構泥臭いのが好きですね。言葉とか、ラップのリリックみたいな。

神門って知ってますか。この人の言葉とか、聞いていたら考えさせられるようなものが好きで。

「夢をあきらめて現実を生きます」という曲とか「一握り」ってやつとか、一生懸命生きている感じで、何か現実味があって。

こういうのを聴いて、アシスタントにも伝えたいなと思っています。

自分がやってきたことを言っても、昔と今はやり方が違う。この詞って今の言葉だったりするから。

でも考え方は昔と変わらないのかなって思ったりします。

昔からそうなんですけど、曲とかで自分を奮い立たせてますね。

自分の写真は泥臭くないんだけど、考え方は泥臭いかもしれない。そういうのを聴いていたら、「何かやらんとあかん」と思うんで。

あとは都築響一さんとかも好きです。収集癖みたいな。

誰もが目を向けないところに特化して延々と編集するやり方とか、刺激を受けています。

Osamu Yokonami/横浪修:

1967年、京都府舞鶴市に生まれる。1989年に文化出版局写真部入社。

独立後は、写真家として自身のレーベルやスウェーデンのLibrarymanなど、海外の出版社からも写真集を刊行。「Assembly」シリーズをはじめ「100 Children」や「1000 Children」、「PRIMAL」など数々の作品集を出版し、カリフォルニアのDe Soto Galleryや、台湾の新光三越などで個展を実施している。

また、2023年にはKYOTOGRAPHIE 京都国際写真祭のサテライトイベント KG+でも個展が開催され、国内外から多くのファンが来場した。瑞々しさとユーモアに満ちた豊かな写真表現には、独自の世界観が息づいている。

WEBSITE:www.yokonamiosamu.jp

【Lula BOOKS “Assembly Teshikaga” by Osamu Yokonami】

RELEASE DATE : 2023年10月18日(水)

PRICE : ¥5,940(税込)

SPECIFICATION : ハードカバー / H248mm×W192mm / 104ページ

ISBN:978-4-910889-08-5

PUBLISHER:Lula Japan Limited.

AVAILABLE TO BUY FROM:

Lula Japan Webstore

lulajapan.stores.jp

その他全国書店・CDショップ・オンライン書店など

【Osamu Yokonami Photo Exhibition “Assembly Teshikaga”】

DATE:10月19日(木)〜11月7日(火)

※水曜定休

TIME:12:00pm〜7:00pm

PLACE:BOOK AND SONS

ADDRESS:東京都目黒区鷹番2-13-3 キャトル鷹番

ADMISSION FREE

A photographer Osamu Yokonami’s the latest photo book ‘Assembly Teshikaga’ is released on 18th October (Wed.) as the fourth volume of the publishing project “Lula BOOKS“.

A photo exhibition commemorating this will be held at BOOK AND SONS from 19th October (Thu.) to 7th November (Wed.).

Prior to this, Lula Japan Web conducted special interview with Yokonami.

Since deciding to become a photographer, he encountered various encounters, changes in his surroundings, and the occasional big wall that looms over him.

Even if such a situation, his firm determination has never wavered.

This time he spoke gently one by one in honest words about what he has felt in his steady progress.

When did you first get a camera?

Please tell us how you came to love photography.

When I was in elementary school, my parents had a Konica camera, and I would take pictures by myself when we went out with my family.

Well, I wasn’t into it at that time.

It all started when I was in the second grade of junior high school or so, when I saw a TV drama titled ‘Genta Ikenaka 80 kilometers’ starring a news agency’s exclusive photographer played by Toshiyuki Nishida. And there was a scene that he was told by his boss in the morning “Go to Hokkaido now” and he went to Hokkaido in the afternoon.

My father was in the Japan Self-Defense Forces, and when I was a child, I believed that a regular company employee’s job was to go to the office and work at a desk, so I thought it would be nice to be able to go to various places for work.

I just thought photographers were great.

What kind of pictures were you taking when you first got into cameras?

At that time, I was looking at camera magazine titled CAPA and taking pictures of landscapes and so on without any consciousness at all, just learning by watching others.

Then, when I was in my first or second year of high school, my parents bought me a single-lens reflex camera, and I started taking photos in earnest.

From that time, I had vaguely decided to go to photography school, and people around me said, “What are you going to do with a camera?”.

But I believed that in the end, if I tried, I could do it, and if I gave up at the beginning, I would never be able to do it.

Were there any difficulties in pursuing your career in photography?

When I was an assistant, I had no money, and it was also tough when I was in Osaka.

I had no idea what was going to happen because I couldn’t see the future.

Nowadays, if you share your works throughout social network or something, you might get a job, but in the past, the hurdles were much higher.

It would be nice if you could become a photographer, but if not, it would be very hard. However, I thought that if I didn't try to do it, I wouldn't be able to become one, and I would have to keep trying.

There was one time when I was in Osaka doing unrelated work and I got sick of photography.

At first, I got a job at a publishing company that made company brochures and admissions brochures after I graduated from photography school, and I took pictures of meeting scenes, factory machines, and portraits.

It was first time to work for me. I had to work every day from morning to night from Monday to Saturday, and I also had to work on Sundays twice a month, so I hardly get any time off, which made me think that working is quite difficult.

After that, I worked as an assistant to a personal photographer, but there wasn’t much to do even though I was in the office from morning to night and money was tight.

So, I had to dig into my savings and work part-time at night for a printing company, and my mind gradually became desolate, wondering why I was doing all this.

Then I started saving money to go to Tokyo, living on the second floor of a house like a company warehouse in the city. The house was dirty, and there were even weasels in the warehouse.

Even so, I was ready to have no other job than being a photographer.

I was about 22 years old at that time.

What made you want to go to Tokyo?

At that time, everyone basically entered a studio in Tokyo after graduation from a technical school.

I went to Tokyo about 2 years later than them, and I didn’t want to work under them, so I joined the photography department of Bunka Publishing Bureau, no one would be there.

It was exciting to see all kinds of people come in, including people in the fashion industry, photographers active in the front lines, and people returning from abroad.

At that time, it was still the bubble era, and it was an amazing world.

Did your state of mind change as the environment around you changed dramatically?

My determination to become a photographer has never changed.

It is no longer there, but there was a building called Bunka Publishing Bureau with about 6 floors.

The editors were all wearing black, like “COMME DES GARÇONS” or “YOHJI YAMAMOTO”, and it was that kind of era.

The second floor was general affairs, the editorial department was on the third and fourth floor, the makeup room and studio were on the fifth floor, and there was a sort of photography department on the sixth floor. There was a corridor that everyone, including outsiders, had to pass through to get to the studio.

So, one day I asked the head of the department if I could put my photos there.

No one had ever done that before, but I thought it would be nice to have my works seen by the editorial staff.

After that, I worked as an assistant to Kazuyoshi Nakagomi for about a year and half, and there was a project to go to Thailand for a magazine titled MR. High Fashion.

Perhaps the editor-in-chief at the time had seen my picture on the corridor and asked me to do interview and documentary photography works as an assistant separate from my master’s shoots.

At that time, generally an assistant had to be at the site about 3 days before master to prepare.

It was a very extravagant project in which I went to there ahead and spent a day walking along the Chao Phraya River in Bangkok with the writer to take pictures, and it ended up being about 12 pages.

That was amazing to me as an assistant, and the layout was combined with my master’s fashion pages. My photos were documentary, so they looked stronger than the fashion.

The seeds I had planted when I was at the Bunka Publishing Bureau led to this opportunity a year or 2 years later, and I realized that I should always do what I feel like doing.

If you’ll keep taking photography for now, the recognition will follow.

So, I see that you have been publishing a collection of your works continuously and expanding your work both in Japan and abroad.

I feel that what I personally do and the world of photography in Japan are different.

In Japan, the maniac world is difficult to be accepted, and I would prefer to get my work out international.

For example, my commercial photography is recognized in Japan, but in other countries, people look at my work with an impartial attitude because it is not that well known.

If there are any opportunities for me outside of Japan, such as publishing a book of photographs via Libraryman, I will jump at them.

As I do so, I get more recognition internationally, and it becomes more powerful as it grows into a single piece of work from a general aspect.

I think the only way to achieve this is to keep going.

You have continued to take portraits of children with fruit on their shoulders, as well as the ‘Assembly’ series that you have just published.

I think to myself that rather than doing many different things, it would be better to do something persistently specific and strengthening something to get to a place where no one can catch up with me.

I recently did a job in China because they recognized me.

It was a photo shoot with about 15 children and was very tough because they totally wouldn't listen to me.

But I think the fact that I can work internationally in this way is a result that I have been spreading these kind of seeds for several decades.

What is your favorite country?

I like Thailand. The food is great there.

The city is full of people, and it has the atmosphere of the 30s to 40s in the Showa period, which makes me feel comfortable, and the people are smiling.

I like Bangkok because the people are so kind.

This is also connected to your interest in cameras because you can go to many different places from the beginning of this interview.

That's for sure.

I also take various things and many people as good examples to look back on.

It is difficult for a photographer to stay at the forefront for decades.

As they become successful, there are people who start to talk a bit too bossy or work roughly. I try to be careful about that during my work.

Maybe I was a little like that when I was younger, but I tell my assistants not to be like that.

From my 20s to 30s, I did most of the Japanese fashion magazines, so sometimes the themes started to overlap. Then I became more and more trapped in what I had to do, and there was a time when I thought it would be no good to continue doing only magazines.

From there, in my early 30s to around the age of 33 or 34, I tried to reduce my magazine work while also doing advertising work when I had the chance, but in the old days, photographers were very separated into those who worked for magazines and for advertising.

At that time, advertising photographers had a superior image, so it was very difficult for me to get there. I even went to show my book to a producer on my own, but I was told that the only one person in a 100 could get a job, and I had a tough time getting through that.

Then, when I brought a collection of my photographs to a publishing company because I wanted to work like an artist, and once they asked me, “Do you want to make a book of photographs, or do you want to do it as a job?”

I thought that was how they looked at me.

I was thinking that work for magazines was something completely different from the other because it was not something I created all by myself, and it was something I did in cooperation with someone and was paid for.

Then I realized that I had to start making things into something that people would want to ask me to do it, so I began to make a conscious effort to create my own work.

Do you have a different approach to fashion photography and shooting your own work?

There are things like spontaneous or not, fashion is how you want the outfit to look, and so on.

Also, since we work as a team, we get other people's opinions.

With a magazine, the theme is already set up, so we work based on that.

But with my own creations, anything is possible, and there a 360-degree direction of approach.

The decisions I make by myself are everything, so all the choices I make come back to me.

Honestly, which one is harder?

Actually, it may be easier to do something that you are asked for, because the direction of the work has been already planned.

But now I have a direction for my own work, so I just set some goals and shoot backwards.

Everyone says that they don't know what to shoot, but I have already started to choose what I want to shoot, so all I have to do is to create.

For example, when I go to the bathroom, or when I'm spacing out in the bathtub, or any other moment that occurs to me, an idea came up like “This would be interesting”, and I'll give it a try.

If I get a good feeling from what I'm doing, I keep on trying it. It's all just an idea.

Do you have any habits that you consciously input when thinking of ideas?

Before, I used to go to Daikanyama Tsutaya Books or Aoyama Book Center to read foreign magazines and visit exhibitions when I had time.

I refer some fashion magazines since they had different trends in visuals, lighting, and the way they were shot.

I think somehow my photography has always changed from time to time.

For example, I would take advantage of lighting trends that everyone else was following, but I would do it half a year later.

There was a time in Japan when it was considered acceptable to photograph the city of Tokyo as if it were London or Paris, but I had my doubts about that.

Since I am Japanese, I thought it would be better to shoot a photography that only Japanese could do.

Nobuyoshi Araki and Daido Moriyama are accepted around the world because of their Japanese originality.

The style is totally different, but I admire that kind of thing.

I am consciously trying to do things that I can shoot because I am Japanese, and I am doing things like ‘1000 Children’ myself.

How do you find inspiration now?

Are there any artists or creators that inspire you?

I am not really conscious of it, but like when I ride trains and bicycles, and walk around town.

I think I get a lot of ideas from those habits.

I also like muddy things. Like words and rap lyrics.

Do you know Goudo? I like his words and the kind of things that make you think when you hear them.

Like the song "I'm going to give up on my dreams and live in reality" or the one called "A handful," it's like he's living life to the fullest, and there's something realistic about it.

I would like to listen to these things and pass them on to my assistants.

Even if I say what I have done, the way I used to do it and the way they do it now are different. These lyrics are in today's language.

But I wonder if the way of thinking is the same as in the past.

I've always been like that, I inspire myself with songs and such.

My photos are not muddy, but my way of thinking may be.

When I hear them, I think, "I have to do something”.

I also like Kyoichi Tsuzuki. Like his collecting habit.

I am inspired by the way he specializes in editing endlessly in areas that no one else pays attention to.

Osamu Yokonami:

Born in Maizuru City, Kyoto Prefecture in 1967, he joined the Photography Department of Bunka Publishing Bureau in 1989.

Since becoming an independent photographer, he has published photo collections by his own label and other publishers, some of them overseas, such as Libraryman in Sweden.

He has released a number of publications, including the ‘Assembly’ series, ‘100 Children’,‘1000 Children’, and ‘PRIMAL’, and has held solo exhibitions at De Soto Gallery in California, Shin Kong Mitsukoshi in Taiwan, and other venues. In 2023, his solo exhibition was also held at KG+, a satellite event of the KYOTOGRAPHIE International Photography Festival, which was attended by many fans from Japan and abroad.

His abundant photographic expression filled with freshness and a sense of humor is imbued with a unique worldview.

SHARE

RELATED ARTICLES

LATEST TOPICS

PICK UP

-

- Fashion

- 09.Feb.2026

-

- Fashion

- 16.Feb.2026

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- Beauty

- Encounter

- 07.Jan.2026

-

- Fashion

- 17.Feb.2026

-

- Art&Culture

- 20.Feb.2026

-

- Encounter

- 17.Mar.2026

-

- Beauty

- 19.Feb.2026

-

- Fashion

- 26.Jan.2026

-

- Beauty

- 09.Jan.2026

-

- Beauty

- 08.Jan.2026

-

- Fashion

- 19.Jan.2026

-

- Fashion

- 05.Jan.2026

-

- Encounter

- 18.Dec.2025

-

- Fashion

- 13.Nov.2025

-

- Fashion

- 03.Dec.2025

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- Beauty

- Encounter

- 01.Oct.2025

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- 04.Nov.2025

-

- Fashion

- 31.Oct.2025

-

- Fashion

- 08.Sep.2025

-

- Art&Culture

- 01.Aug.2025

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- 13.Jun.2025

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- 13.Jun.2025

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- 04.Jun.2025

-

- Fashion

- Art&Culture

- Beauty

- Encounter

- 22.Apr.2025